Despite what the financial media like to tell you I believe investing in shares directly is a loser’s game.

With the UK and global stock markets at record highs and interest rates on savings at record lows, amateur investors are stuffing their SIPPs and ISAs with direct shareholdings in the expectation of strong returns or a high yield. Often this is on the back of hot tips from the weekend press or publications such as Investors Chronicle.

I believe this trend is going to lead to tragedy, with investors’ lifetime plans ruined from a mix of greed, ignorance and naivety.

First, let me be clear, I am not saying a global stock market crash is imminent; just because stock markets are at all-time highs it doesn’t mean a crash is around the corner. One could be but it doesn’t automatically follow as night follows day. There is as much chance of the bull run that started in spring of 2009 continuing as there is of it correcting.

Also, as my investment philosophy states, I believe shares are the most appropriate investment for higher long term returns and that buying and holding through stock market crashes and the subsequent recoveries will generate greater returns than trying to be clever and second guess the markets.

The reason why I believe investing in shares directly is a loser’s game is twofold: a lack of diversification and the inevitable behavioural mistakes that will follow.

A lack of diversification

Another way of expressing a lack of diversification is having all your eggs in one basket. Most direct share investors hold only a handful of shares which are typically in the FTSE100. Favourites tend to be global banks like Standard Chartered, mining stocks such as Rio Tinto or defensive companies with attractive yields such as British American Tobacco (if the ethical hurdle of investing in a cigarette manufacturer can be cleared).

This lack of diversification is a double-edged sword: it brings extra risk; if the FTSE100 falls it takes every company down with it. It is also an opportunity cost; by investing more in one market less can be invested in overseas markets which may enjoy greater growth opportunities than the UK stock market.

There are too many examples of ‘strong’ companies seeing their share price plummet on the back of surprise news to see any single share investment as a certainty. Once a share falls on the back of company-specific events (as opposed to market-wide corrections) they rarely recover anywhere close to their pre-fall highs. Consider:

-BP; £6.39 a share before the 2010 Deep Horizon oil spill, now trading at £4.83 (at the time of writing).

-RBS; £68.85 a share before the 2007 banking crisis, now trading at £2.68.

-Tesco; £2.97 a share before the 2014 accounting scandal, now trading at £1.88.

These are just a few in a long line of stock market darlings that fell dramatically overnight. Investors in these shares would have had no way of foretelling the events that led to their downfall and so would have lost significant value by not diversifying.

At least if you held onto these shares your investment would still be worth something today. If you had the misfortune to invest in the likes of Woolworths, BHS and MFI your shares would now be worthless. As this article from investment managers, Schroders, shows only 28 of the original 100 companies that made up the FTSE100 at its launch in 1984 remain there today (admittedly not all companies would have become insolvent, some would have merged or been acquired and others have fallen out of the top 100).

And if you think you can identify the winners from the losers and predict the future before it happens (as highly paid fund managers like to think they can) this article states that

“only one in 25 companies are responsible for all stock market gains. The other 24 of 25 stocks — that’s 96 percent — are essentially worthless ballast.”

In other words, you have to be either very good (not likely) or very lucky (highly unlikely) to identify and hold the 4% for long enough and through the ups and downs of the stock markets to get market-beating returns. For the rest of us who know we aren’t that good or that lucky, we are much better off buying and holding a globally diversified portfolio of index trackers at low cost, to a degree of risk that we are comfortable with and that is consistent with the returns needed to achieve our goals.

Inevitable Behavioural Mistakes

The other reason I stated above that I believe investing in shares directly is a loser’s game is the inevitable behavioural mistakes.

I would confidently bet that anyone who invested in the likes of BP, RBS and Tesco watched their share price start to fall and, rather than cut their losses, waited just in case they recovered. So they waited and continued to watch as the share price fell further until it either became worthless on insolvency, they sold for a greater loss than had they reacted sooner (or not held them directly at all) or are still holding onto them just in case they do recover to their former glory (not likely anytime soon).

As I explained to my wife the other day who was experiencing something similar, investing is contextual: why is the investment being held, how long is it to be held for and is the risk of loss greater than the benefit of any gain?

If you are likely to need the value of any investment in the near future it is almost definite that the impact of a loss in value will be much more significant than the benefit of any potential increase over that timeframe. When losses occur they are usually sharper and quicker than speed and magnitude of gains (look at the angle of the downward movements compared to the upwards movements on this FTSE100 chart to see what I mean. You may have to change the time period to ‘max’).

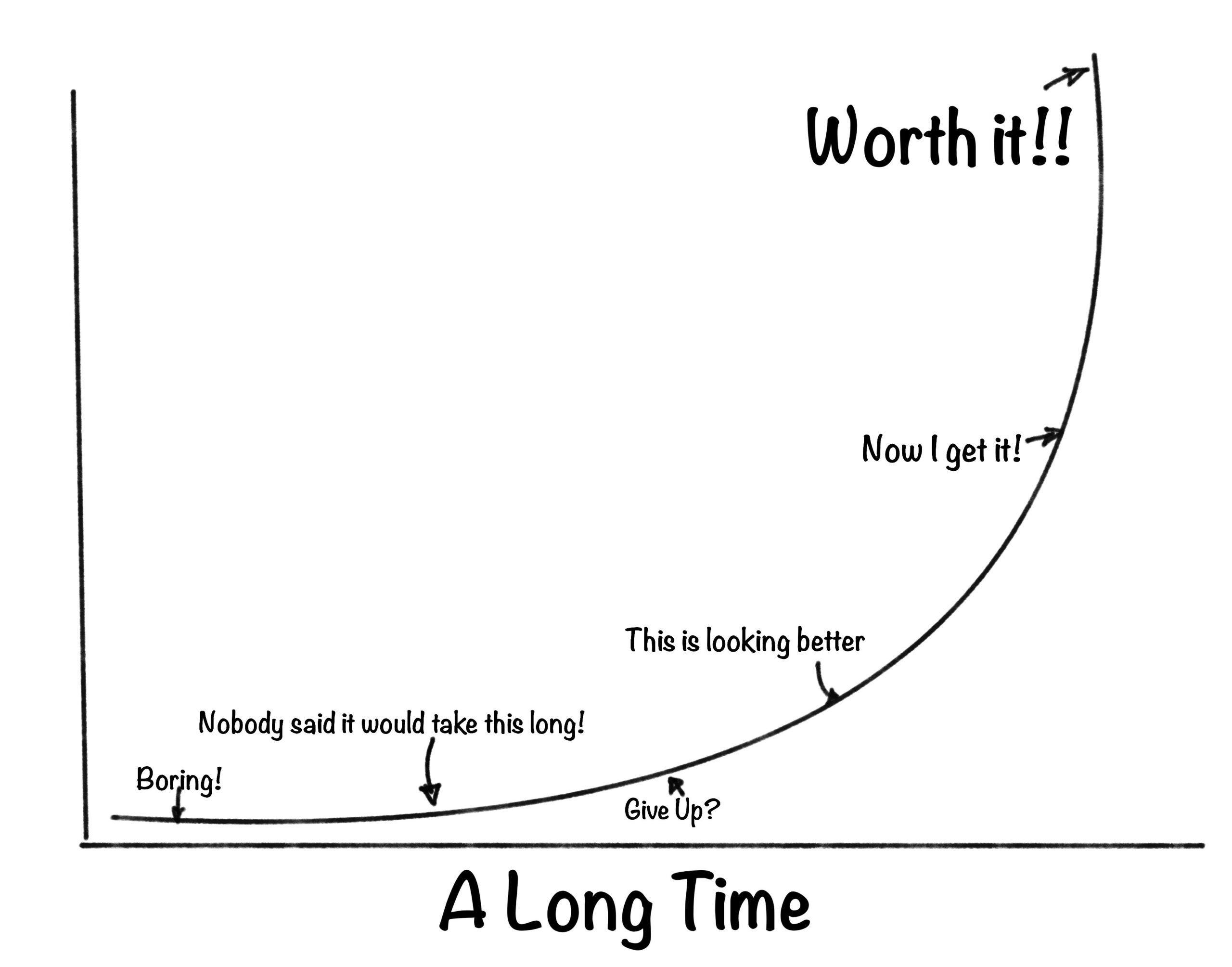

Sensible investors know what returns they need from their investments, know they can’t control or time markets and understand that the key to successful investing to is to buy globally at low cost and have the patience and discipline to hold for the long term.

As legendary investor Warren Buffet explained,

“the stock market is a device for transferring money from the impatient to the patient.”

Photo by Joshua K. Jackson on Unsplash