As interest rates on savings accounts begin to drop again, many UK savers feel worse off. After a prolonged period of extremely low rates, savers began to feel rewarded with interest rates of 5% or higher. Those higher rates, however, were temporary; we’re now seeing rates fall in line with the Bank of England’s Base Rate cuts.

While savers may feel they are once again the victims of the Monetary Policy Committee decision-making, that viewpoint is focusing on the wrong number.

Savings Rates Are Falling, But So Is Inflation

After an extended period of ultra-low interest rates, savings products regained their attractiveness in 2023 and early 2024. But now, as inflation moves closer to the Bank of England’s 2% target, the Bank is continuing to cut its base rate, and savings providers are following suit.

This might feel like a return to bad times for savers. But if inflation is falling too, the impact on your real return, that is, your return after inflation, is less dramatic than it seems. In fact, in many cases, it may be improving.

Savings Rates Are Usually Lower Than Inflation

Over time, savings accounts are not designed to deliver above-inflation growth. They’re designed for security and liquidity, rather than wealth building. As a result, the interest rates they offer often fall below the rate of inflation, especially in periods of rising prices.

If you earn 1% interest but prices are rising at 3%, your purchasing power is declining by 2% per year. This isn’t unusual; in fact, it’s been the norm for much of the past 20 years. Most UK savers have been losing money in real terms without even realising it.

There are exceptions, such as years when inflation fell below savings rates, but these are relatively rare.

Why the Real Return Matters

It’s easy to focus on the interest rate printed on your savings statement. But that rate doesn’t tell the whole story. Inflation erodes the buying power of your money, and if your savings aren’t keeping pace, they’re effectively shrinking.

The real return is calculated as:

Real Return = Savings Interest Rate – Inflation Rate

If this number is negative, you’re losing purchasing power. If it’s positive, your savings are growing in real terms.

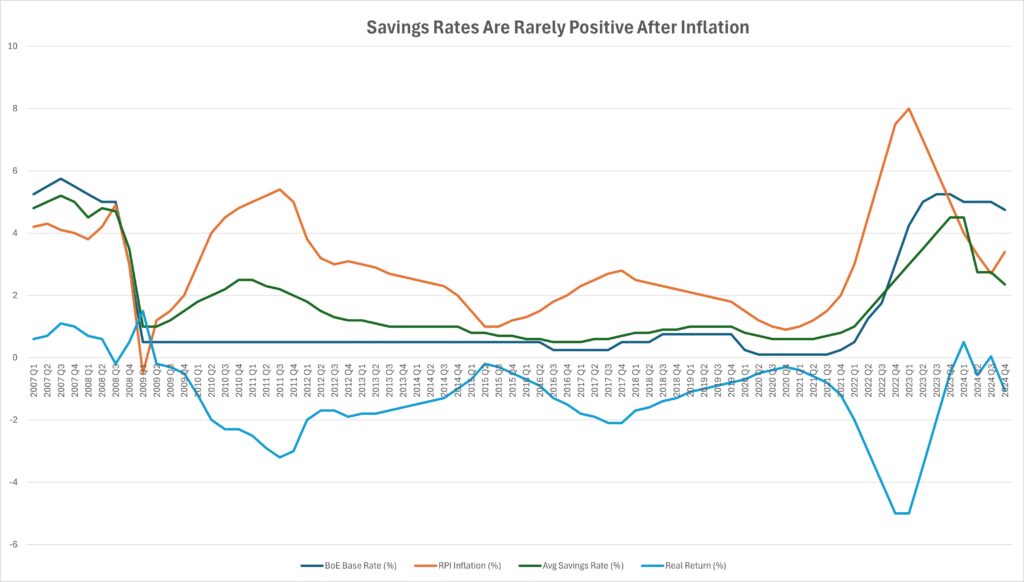

Illustrative Comparison: Savings vs Inflation Since 2007

To illustrate this, the following chart shows the illustrative average savings rates, RPI inflation, and the Bank of England base rate from 2007 to 2025. While savings rates vary by product, these figures help show the general relationship between interest and inflation. Click to Enlarge.

The blue line is the Bank of England Base Rate, the green line a typical headline savings rate, the orange line the inflation rate, as measured by RPI, and the blue line the real return. You can see that the real return spent most of the 17 years in negative territory.

Note: Savings rates are illustrative. Figures for 2025 are forecasts.

Sources: Bank of England, ONS, RateInflation.com, YCharts

What This Means for Savers

So, are falling savings rates bad news? Not necessarily.

Because savings rates are correlated to inflation, the real return on your savings will be similar. It may still be a negative real return but you are not necessarily worse off than when savings rates were higher. Remember, too, that the primary purpose of savings is to provide security and liquidity, not generate growth.

Key Takeaways:

-

Focus on the real return (interest rate minus inflation), not just the headline rate.

-

Understand that savings accounts typically don’t beat inflation in the long run.

-

Falling rates can still deliver better value if inflation falls too.

Practical Steps for Savers

Here’s how to think about your savings now:

- Review of Your Accounts: Regularly review the interest rates you are receiving, especially if you initially chose a high headline figure with a bonus. Banks and building societies don’t reward loyalty, so switching accounts may offer higher returns now.

- Be Cautious with Fixed-Rate Accounts: Locking in now could be beneficial if you believe rates will continue to fall, but stay flexible. Spreading money between instant access and fixed-term accounts can give you a spread of liquidity and higher rates.

- Remember the FSCS Limit: The FCA authorises and regulates savings accounts, which protect up to £85,000 per individual if the banking institution becomes insolvent. Aim to keep within this limit. Remember, though, it is per banking institution. Be mindful of bank subsidiaries operating under one institution, RBS and Natwest, for example.

- Consider Cash Management Services: there is now a range of online services that do much of the work for you by moving your money to different savings products on your behalf when terms expire. The provider charges a fee for the service, making it more suitable for larger balances where spreading money across multiple accounts to stay within the FSCS limit is more challenging.

- National Savings & Investments: The NS&I offer a range of tax-free and taxed savings products, the most well-known being Premium Bonds. These offer a very secure home for your money, but you are likely to find that the interest you receive is lower than the average savings account.

- Keep an Eye on Tax: Interest counts as income. If you have income less than £12,570, the first £5,000 of interest will be tax-free. For income between £12,570 and £17,570, the £5,000 is reduced by £1 for every £1 of income over £12,570. Beyond that, Basic Rate taxpayers have an annual Personal Savings Allowance of £1,000, which reduces to £500 for Higher Rate taxpayers.

- Consider Other Assets: For longer-term funds, think about investments that aim to outpace inflation,

Conclusion: Don’t Be Misled by the Headlines

Yes, savings rates are falling. But in the context of falling inflation, that might not be as negative as it seems. Over the long term, the real return, not the nominal rate, is what determines whether your savings are working for you.

So next time you hear that “rates are getting worse,” ask: worse compared to what?