Adults in the UK do not have enough money in savings. According to the money website, Finder.com, the average person in the UK has £17,773 in savings in 2023. But, less than 50% have less than £1,000. Nearly a quarter (23%) have no savings at all. There are 27 million Brits whose savings would not last more than a month if needed. So, not much cover for rainy days.

Averages are skewed by extremes, and as expected, the rate of savings increases with both age and income. These figures also exclude pensions and investments, but the numbers pose the question, what is a suitable amount to have in savings?

Rules of Thumb & FU Money

Financial planners use the 3-6 months of expenditure as a rule of thumb. That is, having enough money in readily available and safe savings to cover you for 3 to 6 months. That means whatever happens you know you have sufficient money to cover a loss of earnings for a period of time. Be it from unemployment, illness or accident.

This figure will therefore vary depending upon the cost of your lifestyle. It could also be adapted to include only essential expenditures: mortgage/rental payments, utility bills, food etc, not discretionary items: entertainment, holidays, clothing etc.

Another way of looking at it is having enough to be able to quit your job, have a change of direction or start your own business. This is less elegantly referred to as ‘FU Money’ because you can tell your employer what you think about their job. For which, the length of time may be much longer, a year or two perhaps.

What If You Are Older?

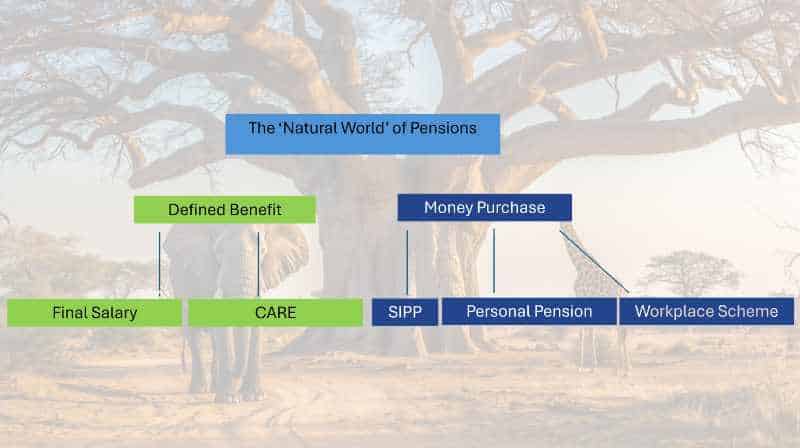

If you are nearing, or in retirement, the need to replace lost income with an emergency fund becomes irrelevant. You still may want to have enough money to quit your job, but by this time, retirement is more likely to be the next chapter. And, hopefully, you will have enough in pensions and investments to provide your financial freedom and security.

That is not to say savings are not important at this stage of life. They are, but the need to draw on savings will be different: to replace cars, to fund repairs or to pay for medical treatment rather than wait for the NHS.

For anyone relying on withdrawals from their private pensions in retirement, it is also good practice to have enough in savings to fund a year’s worth of expenses during times of stock market declines. This allows pension funds to recover unencumbered by regular withdrawals.

What About A No-Savings Approach?

Some financial advisers and planners argue the case that the upward trend of stock markets provides sufficient return over the long term to negate the need for savings in retirement. In fact, they say, inflation is the greater risk to retirement wealth, so savings should be kept to a bare minimum. Yes, they accept stock markets have their declines but as long as a retiree drawing down from their pensions won’t be financially destitute, these falls will be ridden out.

I am uneasy about such an aggressive approach to retirement savings. Not that I don’t believe in the future of stock markets; history evidences that a portfolio invested in stock markets is the greatest defence against inflation. For the reasons explained below, I prefer to see a more substantial savings buffer.

An Uncomfortable Amount

My favourite writer on the subject of money, Morgan Housel, suggests having an uncomfortable amount of money in savings. A balance that feels a bit too high. This isn’t ignoring investing to benefit from the majesty of compounding returns, it’s a failsafe against the expected not happening, of not having to do the wrong thing with your money at the wrong time. Or, as Morgan Housel refers to it, as a margin of error.

We can’t know what the future holds; we can forecast and best guess but for many things there remains sufficient probability that we will be wrong. Having more money in savings than feels intuitively sensible is a hedge against being wrong.

In the years preceding the Great Depression Americans had just enjoyed the Roaring ’20s, a period of economic boom fuelled by innovation and consumerism. The stock market was riding high, until reality hit on Black Tuesday, 29th October 1929. From top to bottom, the US stock market lost nearly 90%. All but a small part of many Americans’ hopes and dreams gone in two and a half years. A lifetime to build up, a blink of an eye to lose.

Black swan events are those rare, unpredictable occurrences that shake humanity to its core. In living memory, there have been only a handful: two world wars, the Great Depression, the Credit Crunch and COVID19. An intellectual minority forecast these events in the abstract but the timing and effect shook the world when each happened.

By definition, we don’t know the nature of the next Black Swan event but preparing for it by having surplus savings provides insurance. This insulation avoids having to do the wrong thing at the wrong time. For retirees, this can also translate into giving up the flexibility of an invested portfolio to the less flexible but more secure annuity income.

Security, The Foundation of Risk

Paradoxically, the more secure a base, the greater the opportunity to take risks. When I set up my business in 2016 I didn’t know where my first client was coming from, I also had an 18-month-old son at the time. What provided me with the confidence to take the plunge was the comfort blanket of having built up sufficient savings and the knowledge if all else failed I could find a job. Without those two foundations I doubt I would have made the leap of faith and risked the business failing.

Anyone with a large amount in savings can afford to take additional risk with their invested assets. They know that if the markets go against them for a period of time they are able to ride out the downturn until the inevitable recovery. A large savings balance also provides the opportunity to react positively when these Black Swan events occur, to invest at bargain prices when everyone else is selling.

A Good Night’s Sleep

Money and emotions are conjoined. Whether it is fear, greed, pride or envy we all have an emotional attachment to money that shapes our decision-making and sense of financial wellbeing.

The technically correct advice to someone may be to invest a certain proportion of their money but if doing so causes them to worry more then should they do so? The financial planning purist may argue that our duty is to adopt the technically correct plan for the financial benefit of the client. It is our job to educate the less informed so that through new knowledge they cease worrying.

I’m unsure if that is the best approach. As I have explained to clients on many occasions if, after any of our interactions, they feel more worried I’ve not done my job properly. Is a better plan one that is technically perfect, and the client accepts with deference, if not full emotional commitment, or one that is less optimal but enables the client to sleep at night?

It is arguable both ways, but my preference is for a client who will sleep at night and has a plan that is mostly right.

With all this in mind, how much should you have in savings? My answer is enough to balance the three-legged stool of security, peace of mind and the confidence to do the optimal thing with the rest of your money.