Talk to anyone of a certain age and they will remember with a chill down their spines the inflation and high mortgage interest rates of the 1970s.

When you bear those scars, the fear of a return of 20% inflation re-ignites every time there is the hint of an increase in inflation. Even if that generation is now well into retirement and may not have the mortgage debt that crippled them 50 odd years ago, the spectre of large increases in the cost of living is not something they wish to repeat.

So What Happened in the 1970s?

Other than being a decade of long hair, longer trousers and shorter shorts (on footballers anyway), the 1970s were a melting pot of socio-economic change that created an inflationary perfect storm.

- The collapse in 1971 of the internationally agreed Bretton Woods system for managing currency valuations led to failed attempts to bring rising prices under control; they largely had the opposite effect.

- An oil embargo by the Arab states following the West’s support of Israel in their short-war against Egypt and Syria caused a big spike in the cost of oil.

- The country was going through a period of economic growth which was further spurred on by Chancellor Anthony Barber and his tax cuts.

- The powerful trade unions lobbied for higher wages to offset the increases in the cost of living (creating a cycle of increasing demand and concomitant increasing prices).

- The launch of the Access credit card (“your flexible friend”) in the UK made purchasing goods on credit possible for more people.

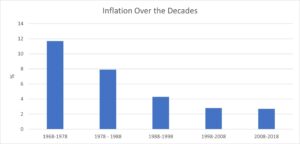

The result of this perfect storm was inflation averaging 13.7% a year during the 1970s.

What Has Happened Since?

Since the 1970s, despite increased consumer borrowing, periodic tantrums from OPEC nations and two Iraq wars, as the chart* below shows, inflation has trended downwards to benign levels.

Will We Experience A Return To the 1970s?

In the aftermath of the Great Financial Crash (the “Credit Crunch”) of 2008, and the policy of central banks the world over to keep economies stable and productive by pumping $ trillions into their respective economies through Quantitative Easing, it was expected that inflation would be the natural successor.

But, as the chart below shows, inflation in the decade post the Great Financial Crash was only marginally higher than the preceding decade but still much lower than the three preceding decades.

Nurses, emergency workers and other public servants who haven’t experienced real wage growth for over 10 years may feel differently, but this low-interest rate/low-inflationary environment has been good news for consumers and mortgaged-home owners.

Now, as we begin to emerge from COVID enforced lockdowns talk of inflation has returned. But will it?

The simple but unhelpful answer is who knows?

The global stock markets had a wobble last month as the US Federal Reserve hinted at possible interest rate increases to stave off inflation; increased interest rates aren’t good news for companies because it costs them more to service existing debt or borrow money, and consumer spending falls when the cost of servicing debt increases).

Reasons Why Inflation May Return:

- There is a wall of money waiting to be spent by the global middle classes who haven’t been able to go on holiday or socialise for the best part of 18 months. They have the means and the motivation to spend.

As any first-year student of economics will tell you, increased demand means increased prices. Increased prices = inflation.

- Brexit does appear to be negatively impacting the cost and supply of goods coming from Europe. If you tried to get any building work done and found the cost of materials has increased or noticed that your favourite food items are not currently in stock it is quite probable that there is a blockage in the supply chain.

Again, as our economics student will tell us, less supply means increased prices, which creates inflation.

- The oil majors can have a hissy fit at any time, for any reason.

Reasons Why Inflation Will Not Return:

I’m prepared to be wrong on this one, but unfettered by the memories of the 1970s, I don’t believe we will see a return to double-digit inflation. Here is why:

- As explained by the former Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney in his book ‘Value(s)’, since the Bank became independent in 1997 it has had greater control and flexibility in its core role of managing inflation.

Unencumbered by short-term political manoeuvrings by Prime Ministers and Chancellors seeking longer in office, they can pull all the levers at their disposal to keep inflation within the 2% annual target.

As shown in the above charts, allowing for periods when inflation has ticked above that target, they have been successfully keeping to that remit.

- These days we spend more of our money on services than we do on goods. According to an Institute of Fiscal Studies 2004 report which compared household spending between 1975 and 1999, spending on typically inflationary items such as fuel, food and clothing fell as a percentage of total household spending, whereas spending on holidays and leisure increased. This report is over 16 years old but the trends have continued.

- A reason why household spending on goods has decreased is not that we are buying less stuff but because the manufacturing of it has moved from the UK to China and other emerging economies. We like to buy stuff but we like it more when it is cheap, the Far East and their cheap labour supply helps us out.

- The pro-private business environment which was created in the Thatcher years, continued through John Major and into New Labour and then into the Cameron years, has increased the competitive environment for low costs service sectors such as travel and entertainment.

Referring to our first-year economics student again, greater supply means lower prices. Just ask British Airways what they think of Ryan Air and Easy Jet.

- We are living through a technological revolution that was inconceivable at the turn of the century when Amazon was failing to make a profit year after year and Facebook was just a glint in Mark Zuckerberg’s eye.

Technology allows us to do more and produce more, all at lower cost. As AI and machine learning evolves more and more jobs will be completed by computers and robots. The thing about computers and robots is they don’t have unions fighting for higher pay and better pensions, which keeps manufacturing costs low. Though, what that means for the employment market is another question entirely.

But What if I’m Wrong, What Is the Best Way to Protect Wealth?

If I am wrong on this, which is perfectly possible because the global economy is a highly complex web of interactions & influences and we can’t know what shocks are around the corner, the best way to protect your wealth from rising inflation is to invest in real assets.

Real assets are those which provide long-term growth above inflation. Property is a real asset but by far the most cost-effective means to generate above-inflation long-term returns is to invest in a diversified portfolio of global stock-market based investments.

However, as stated in the paper ‘The Best Strategies for Inflationary Times‘, May 2021, the authors Neville et al note that not all equities are created equal when it comes to inflation protection. Studying global market returns during periods of high inflation since World War II they found investing his quality companies provided real returns whereas others, particularly small-cap investing did not.

There is logic to these findings; profitable companies with dominant market positions, strong cash-flows and low debt (described as ‘quality’) will be better able to pass on inflation through higher pricing and will be less sensitive to rising borrowing costs. Smaller companies on the other hand are less likely to have the cash flows or ability to pass on rising costs.

Value investing was found to broadly be neutral, whilst momentum investing did have a positive correlation but the results were not consistent enough to draw a reliable conclusion.

Naturally, there will be a chorus of people proclaiming the inflation-busting powers of gold, but in my humble opinion, gold is best left for decoration not speculation.

Oh, and don’t have too much debt. As and when the Bank of England begin to raise interest rates to manage rising inflation, there’s nothing quite like the rising cost of debt to kill the party and stop you spending on gadgets and cheap holidays.

If you want to discuss how you can invest for the long-term please do get in touch.

*Source: The Bank of England